It’s not just millennials and other young people who are souring on free markets (44 percent according to a new poll) — there’s also a growing disenchantment among some conservatives.

Acton Research Director Samuel Gregg explains the conservative angst as rooted, among other things, in the threat that upheaval in market economies presents to the “permanency, order, tradition, and strong and rooted communities.” Conservatives who advocate for free markets should take this critique seriously and “rethink about how to integrate their case for markets into the broader conservative agenda.” And who better to make this case than Edmund Burke himself:

Rather fewer people know that Burke was a committed free trader, a strong defender of private property, and a skeptic of government economic intervention. He once described Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations as being “in its ultimate results,” “perhaps the most important book ever written.” Burke’s literary executors, French Laurence and Walker King, even claimed that Burke “was also consulted, and the greatest deference was paid to his opinions by Dr. Adam Smith, in the progress of the celebrated work on the Wealth of Nations.” When Smith’s magnum opus appeared in 1776, Burke reviewed it for the widely-read Annual Registrar. He sang the book’s praises as a text which managed to achieve that most difficult of goals: to “teach things that are by no means obvious.”

Yet even before The Wealth of Nations’ publication, Burke was arguing the case for greater commercial liberty. In parliamentary debates during 1772, for example, he insisted that the best way for society’s poorest segments to receive enough bread was through a market free of legislative interference. Over twenty years later, in the midst of Britain’s epic struggle with Revolutionary France, Burke penned a carefully-worded memorandum entitled Thoughts and Details on Scarcity to Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger in 1795. Here he explained why the state generally shouldn’t interfere with the market-price of goods, services, and labor.

Burke’s strong belief in economic liberty and the institutions and habits which sustain it are not in doubt. The real question is why he held these views. It turns out that Burke’s support for extensive commercial freedom wasn’t chiefly based upon what we today would call libertarian premises. His main reasons for embracing free markets were those of a conservative.

Read “Edmund Burke’s conservative case for free markets” by Samuel Gregg at the Burkean Journal.

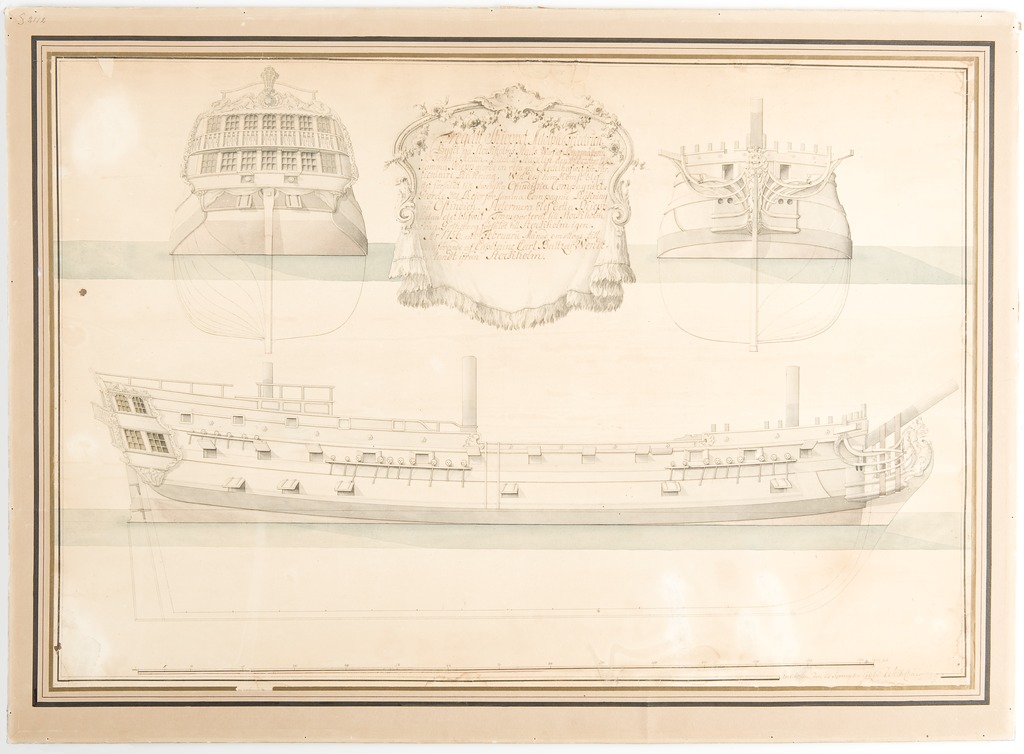

Image: public domain on Wikicommons. 18th century merchant ship.