The endless drama of Brexit – which last week wrote yet another act with Parliament rejecting all possible options – should make many wonders about the future of representative democracy and the dynamics of power in modern society.

Does representative democracy – or its almost interchangeable synonyms like democracy or people’s sovereignty – have a future? The short answer is no, it does not. However, this question has many more nuances than a careless mind might notice. All political regimes will fail; this is part of the dynamics of the historical process. What we need to discover is how and when the process of institutional de-structuring and the reconstruction of a new socio-political model will take place.

1989 was the year in which Western elites declared the victory of a political model – liberal democracy – over the historical process. Francis Fukuyama, the high priest in the so-called New World Order, wrote – two years after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 – that the dialectical process that had governed human history until then had produced his final synthesis. Repeating Hegel and Marx, Fukuyama believed that historical events would not cease; however, from the intellectual point of view, the human mind would be incapable of producing a political regime superior to the Liberal Democrat.

Three years before the fall of the Berlin Wall and five before Fukuyama’s end of history, Margaret Thatcher spoke at the Conservative Party’s annual conference as triumphantly as no prime minister had ever done before. The Iron Lady told her audience that:

From France to the Philippines, from Jamaica to Japan, from Malaysia to Mexico, from Sri Lanka to Singapore, privatization is on the move, there’s even a special oriental version in China. The policies we have pioneered are catching on in country after country. We Conservatives believe in popular capitalism—believe in a property-owning democracy. And it works!

Fast forward 33 years, and we will see that no one is sure of anything. The gears of the historical process once again moved, making liberal democratic regimes a potential casualty of the inevitable changes. China did not become democratic, Cuba did not become capitalist, and nationalism did not die. Singapore – a strange mixture of free-market economics and mild political authoritarianism – may represent a viable alternative. The widespread feeling of malaise felt by Western man means the end of a cycle, but no one knows what is to come.

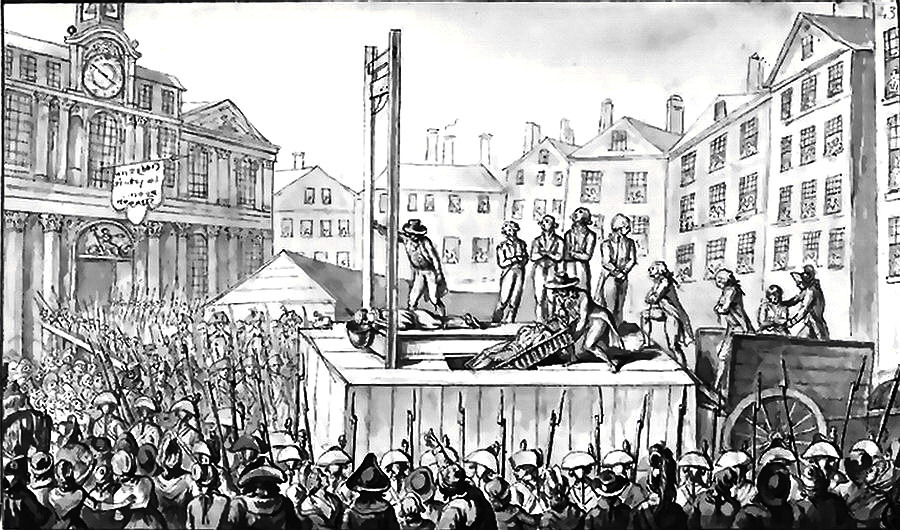

There is a perverse logic that has been commanding human history at least since the French Revolution: The growth of the state’s power. Regardless of the rhetoric employed, every political action has invariably been expanding the power of governing groups over individuals. The state – and the bureaucracy that accompanies it – has increasingly occupied a central role in social interactions and it has slowly replaced old institutions like the Church as mediators of social relations.

According to Bertrand de Jouvenel, the rise of representative governments created a political paradox that cannot be solved. The feudal political structure conferred the sovereignty or the power of political command to a restricted group of men. The political bodies that evolved into the modern legislative branches had as their primary role to counterbalance the power of those who ruled and restrain their action. Medieval parliaments had the power to deny but not the power to command. As the people became sovereign and their delegates came to rule, a vacuum was created in the structure of the exercise of power: If the people rule sovereignly, who will restrain the power of the people?

Commenting about Abraham Lincoln’s famous Gettysburg Address, the Italian political theorist Norberto Bobbio observed that “a government of the people and for the people is certainly possible but a government by the people will never happen.” Power, Bobbio recognized, will always be exercised by small groups or at least smaller than the whole of the political body.

The unequal distribution of power is a fact of nature, and it is neither bad nor good by itself. However, to believe that we live in a sort of society in which people have achieved the maximum of freedom and political control over their own lives is a nocive lie that works out pretty well inasmuch it ensures that people will be kept under control. And why are they kept under control? That is because throughout history every single ruling class needed a way to ensure its legitimacy. In our era, this legitimacy is an unfolding of the myth of democracy.

All nineteenth-century liberal political theory can be understood as an effort to compartmentalize the newly discovered popular sovereignty with the needs of a coherent political regime in which the power of command could be brought under control by itself – checks and balances, for example. Classical liberals like Benjamin Constant undertook a herculean intellectual effort to integrate to the political body social changes while denying democratic egalitarianism as a consequence of popular sovereignty.

The German legal theorist Carl Schmitt correctly understood the inability to reconcile the internal contradictions of a representative political regime in which individual freedom and popular participation coexist in harmony. According to him, parliaments were not made to exercise the power of command, and this reality ended up imposing itself on the material distribution of power within the representative regimes. Designed for the debate and not to rule, parliaments had to transfer their responsibilities to the bureaucracy that was free of possible electoral shocks. Voting might even guide the imperatives of the bureaucratic establishment, but it was impotent to change the essence of its power.

The paradox of democracy – in which the people namely rules and the bureaucracy effectively does – prevails despite the will of political agents. The construction of a bureaucratic authoritarianism under the excuse of democratic progress is not an ideological matter insofar as an ideology does not allow the existence of the bureaucracy’s power; on the contrary, it justifies its exercise for the masses. Ideology confers an emotional veneer and helps to break down resistances toward the relentless exercise of the power to govern. However, ideologies are not the engines of power. Power obeys a dynamics of its own that must be understood to be controlled.

The phenomenon that Schmitt and others observed within the representative democracy’s dynamic is not unique to this political system. Quite the contrary, the concentration of the power of command and its exercise by a ruling class is a constant in all human political associations. What is striking in the case of modern democracies is the accentuation of this phenomenon precisely at a time when the myth of the increase of both individual liberties and political participation has become universal. The more the reality of the exercise of power is covered by rhetorical layers that celebrate the achievements of human rights, the more relentless the control of the bureaucratic state over individuals becomes.

The Catechism of human rights – to use Edmund Burke’s words – serves well to the expansionist objectives of the bureaucratic class. The core of the concept of human rights is the subjection of the whole social body to the needs and demands of the individual subjectivism. The “I have the right” fetishism has led to unprecedented expansion of government power to meet endless demand for rights. With each new right demanded and created, a new department or new agency will be designed to ensure compliance with this new standard. It is not surprising, therefore, that one of the characteristics of modern society is legal anarchy and managerial authoritarianism.

What we have is a widening division between the axis of rhetoric or the justification of political action on one side, and the axis of the exercise of the power of command on the other. The modern political regimes’ inability to answer “who rules?,” “why rules?” and “how rules?” produced an alienation between the ruling class and the rest of the population, or in a nutshell: a class with powers limited only by material reality, but without any responsibility – the very definition of despotism. With representative democracy reduced to a theater of shadows and the real power entrusted to a class far from the control of the polls, there are few incentives to solve the primary problem of the modern political regime.

Until now most of the means used to counterbalance the abuse of power practiced by the elites – and not so much constrain the power of the elites – has been through the electoral route. The different populist movements seek to increase popular participation in decision-making through referenda and other instruments that would enable grassroots pressure on the ruling class. Such policy does not seem to be working and will never work because the disorganized majority does not have the means to break the organized minority control system by playing according to the rules of that same system. As the institutions are established to enable the government – not necessarily despotic – of the ruling class, all the impacts produced by populism will be integrated into the power structure and neutralized by it.

Both Schmitt and the Italian thinkers Vilfredo Pareto and Gaetano Mosca explained why makes sense to be skeptical towards increasing democracy as an instrument to counterbalance the control exercised by the system. Schmitt, for example, believes that the only way the vote could shape the politics would be through a plebiscitarian dictatorship, in which a man would be entrusted with the power to reestablish the political-social order vis-à-vis the corrupt elite’s ruling.

Pareto and Mosca, by their turn, believed in the inevitability of elites, that is, elites are natural to human political organizations. History, according to them, can be explained through the succession of different elites ascending and falling – what Pareto called the circulation of the elites. No matter what happens, an elite has always emerged to govern. Mosca explained that every time a particular governing class is no longer representing the disorganized majority, it is replaced by the government of a new elite and not by the government of the disorganized majority – which would be a contradiction in terms.

The populist proposal – like Brexit – has little or no chance of success since it does not aim to overthrow the power structure and put a new one in place of it. In this sense, it is much more an explosion of incoherent feelings and a revolt against the system than the creation of a functional political proposal. If Schmitt, Pareto, and Mosca are right about the dynamics of power in human associations, then the process of political transformation must go through the construction of a new elite.

A ruling class cannot utterly be destroyed, it needs to be replaced. The dynamics of power will immediately neutralize any action aimed at the annihilation of a ruling class within the system in which elites rule sovereignty. All regular political action takes place through the same channels that enable the elites to govern; the political debate works according to terms written by those associated with the ruling class. No one had beaten the elites by playing by the rules they created. What must be done is to subvert the regime, subvert the power structure. And the only possible subversion of the power system is through the creation of a new elite.

Homepage photo: Wikimedia Commons