As our global economy has grown more technological, connected, and complex, fears continue to loom about an economic future wherein our workers are rendered obsolete—whether by new products and industries, new forms of automation, or more competitive labor forces across the globe.

Struggling to keep up with the pace, we’ve come to embrace technical knowledge and skills-based expertise as the supreme value in many of our educational institutions, crafting a host of STEM education programs and various incentives to prod and prepare our people for the “jobs of the future.”

But while such measures may be wise and necessary, what might we be missing as we prepare ourselves for the challenges to come? Beyond competence in specific trades and foresight about emerging industries, what else might workers need to truly flourish in future society?

In a new research paper, “STEM Without Fruit,” AEI’s Brent Orrell asks whether our approach to professional development has become overly consumed with technical training and cookie-cutter college tracks. While we’ve managed to put a heavy cultural emphasis on STEM education, we now see little focus on the “soft skills” that employers increasingly look for when hiring employees.

“Labor market data and employer feedback suggest that the emphasis on STEM in workforce development is obscuring deeper, widespread challenges to employability relating to noncognitive skills associated with persistence and character, particularly for middle-skill occupations,” writes Orrell. “Employers report a need for employees with these skills and place a higher value on them than on job-specific skills.”

Nobel Laureate economist James Heckmen categorizes these noncognitive skills under the umbrella of “character,” encompassing our ability to properly regulate and restrain our emotions and behavior. For the purposes of Orrell’s study, they represent “the capabilities associated with personality traits and socio-emotional learning.” For others among us, they also connect closely with virtue.

While many of our policymakers and educational institutions may pay little attention to such skills, they are already widely recognized as foundational in many businesses’ standard competency models. For as much as we continue to fret about our technical competency in math and science, companies and researchers continue to affirm that the growing need lies elsewhere.

We don’t need more brainy and sophisticated tech wizards; we need knowledgeable tech workers who have the wherewithal to be virtuous and resilient leaders, innovators, and collaborators. “Massachusetts Institute of Technology scholar David Autor has found that, as technology has advanced, occupations that demand skills such as flexibility, conscientiousness, and social skills are increasingly relevant,” writes Orrell. “This suggests that in a technology-driven, highly automated economy, the most intrinsically human characteristics will, paradoxically, matter most.”

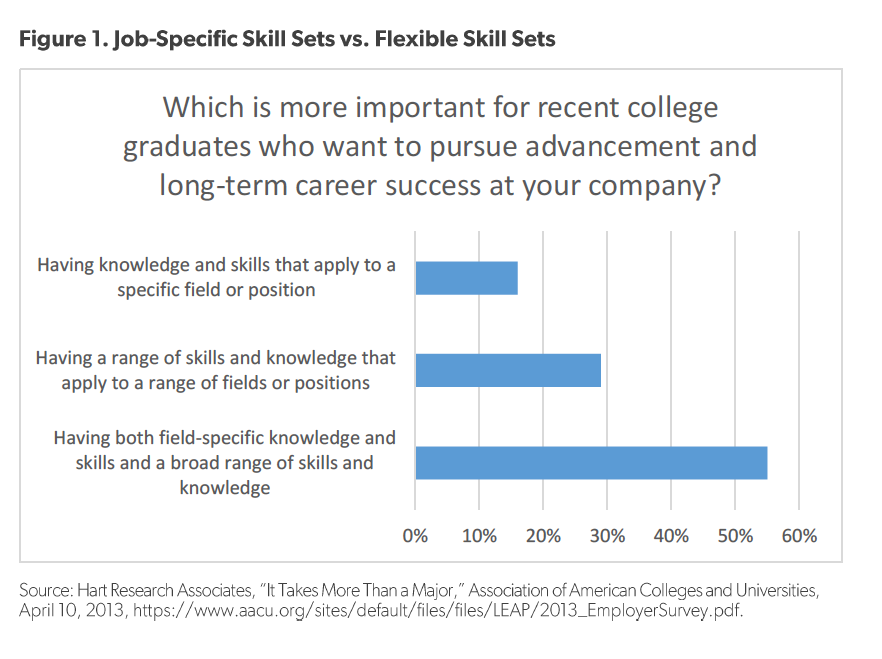

This both-and combination is confirmed by a range of survey data on employer preferences, as summarized in the following chart from the study: But how are we to actually cultivate these skills across our society? If these areas do, in fact, intersect with basic matters of character and virtue, what are the key opportunities for growth?

But how are we to actually cultivate these skills across our society? If these areas do, in fact, intersect with basic matters of character and virtue, what are the key opportunities for growth?

As Orrell points out, much of the research points closer to home than it does our schools and workplaces. “Noncognitive personality skills evolve over time and are heavily affected by parental support and life experience,” he writes. “…Emotional self-regulation, a key to establishing and maintaining interpersonal and professional relationships, is developed in early stages of infancy and is highly related to parental involvement and family functioning in the face of adversity.”

Given a widespread decline in family stability and the steady evaporation of religious and community institutions across America, the challenges are significant. Orrell proceeds to highlight a range of policy reforms and programs to address the need, including increased marriage and relationship education, preschool intervention programs, and various educational strategies to expand our view of workplace readiness. But in the end, all of this has to come as a complement to the rest:

Competence in math, science, and other technical skills are, without doubt, important to individual and national economic success. At the same time, the priority we have placed on technical skill development has tended to obscure or overlook their foundation in noncognitive skills (listening, problem-solving, teamwork, integrity, and conscientiousness).

Noncognitive skills form the basis of all learning and are crucial to an individual’s ability to adapt to evolving personal circumstances and workplace demands. Further, it is precisely these noncognitive skills that, when blended with the high technology that dominates the economy, qualify workers for the fastest-growing, middle-skill, well-paid occupations in fields such as finance, health care, and leisure industries. This pattern suggests the need for a life cycle human capital development strategy that includes education and training but begins in the seedbeds of character and competence: marriage, family, and early learning.”

It’s a helpful correction to our current cultural imagination. Yet while the counter-balancing programs and strategies that Orrell highlights may indeed help broaden and enrich the typical STEM marketing that surrounds us, it all still strikes me as chipping at the surface.

For strong families and strong communities to prosper, our society needs a deeper and greater awakening of sorts—one that connects the spiritual to the social to the economic and beyond. This isn’t something that can be easily planned or manufactured, especially not through government policy. The bigger first step, though it may seem blurry or “impractical,” is to simply transform our thinking and shift our imaginations and priorities to the places and spaces we’re currently neglecting.

We are likely to see an increasingly automated and technological economic future. But if we are to truly flourish and prosper as human persons in a technological world, it won’t just require strong minds; it’ll also require strong hearts.

Image: PHS Robotics 04, Virginia Department of Education (CC BY 2.0)