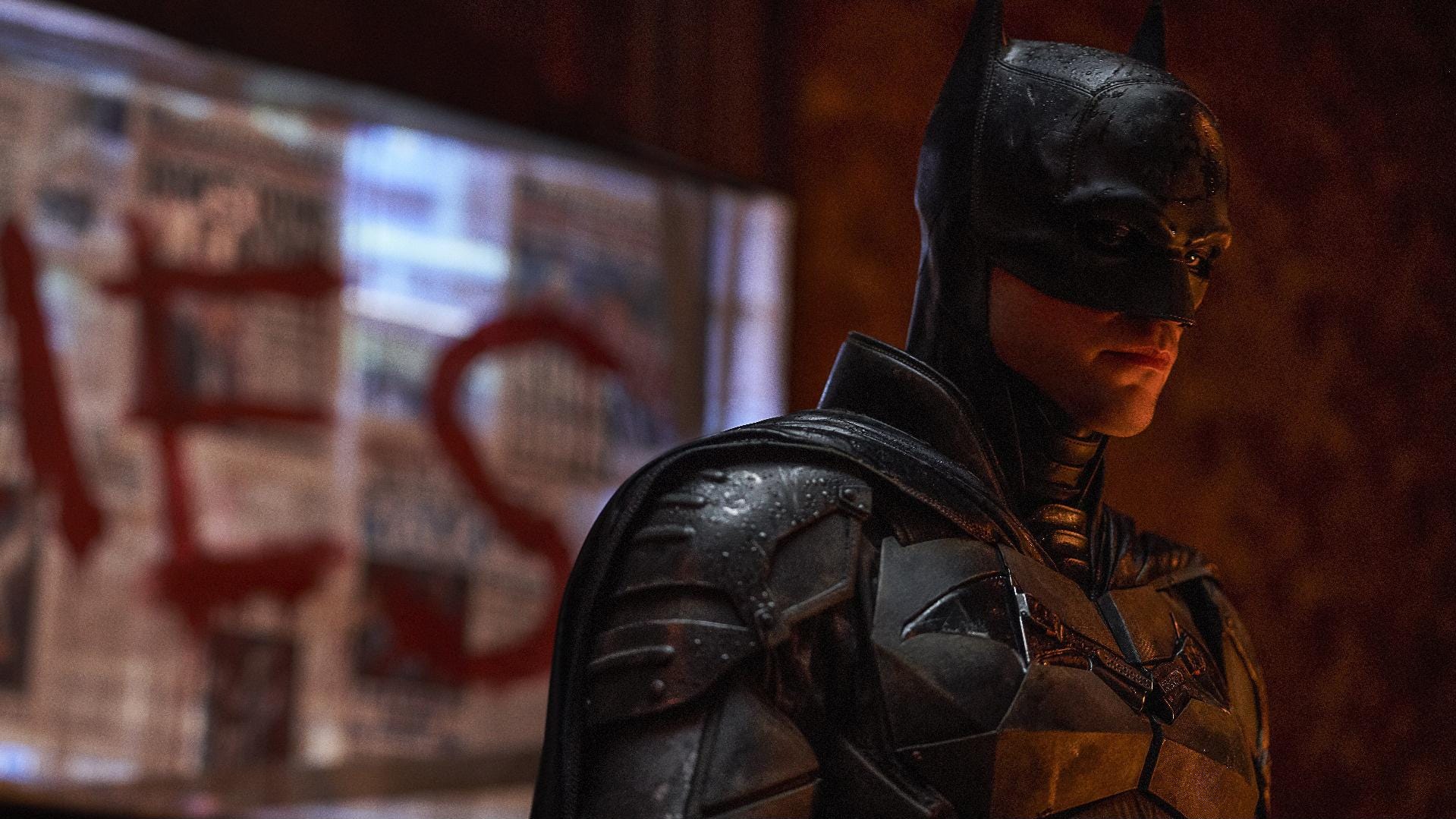

The Batman plunges us straight into the middle of a crisis of faith. Gone is Bale’s confident and charismatic playboy. Robert Pattinson’s Batman hasn’t slept for a week. He journals, sulks, and obsesses over details. A Goth in Gotham—a concept that sounds like it shouldn’t work, but does. The emo overtones match the underlying questions being explored. He records everything he sees during the night, playing and replaying his interactions, plagued by doubts: Is he part of the corruption around him? Is he making a difference? Is it possible to improve the state of Gotham? All questions that mirror the crisis of faith in which we now find ourselves. If institutions cannot be trusted, we lack any mediation between ourselves and our neighbors. Can we trust the narrative generated by mass media? Who has our best interests in mind?

Our corporate pessimism in working out these doubts was underscored in my viewing of the now-blockbuster film. The mob on screen matched the crowd around me. Two groups started fighting directly as the film opened. One was too loud. The other made threats. When the first dumped a drink, the second threatened to pull out a gun (which I think was a bluff), but the first didn’t stay around to find out. They left the theater, with jeers. The rest of us turned back to the picture, ready for a fight, on or off screen.

The questions at the core of the film transcend any specific political narrative. Debates around policing, justice, elections, business, all boil down to whether we can trust those in positions of authority over us and the bodies through which they govern. Gnawing doubts are present in every political and social debate. And the film doesn’t pull any punches, quite literally, in dealing with this crisis. Corruption infects every area of Gotham, causing Batman to question every allegiance. Who can he trust? How, and where, can he find justice?

Justice is just as hard to get in Gotham as in our humble world. The film opens with a very specific view of justice. Batman is effective because he wreaks vengeance against evildoers. His catchphrase, “I am vengeance,” is intended to induce in criminals the very fear they are provoking in Gothamites. Batman wants those criminals to “see him in every shadow.” He strengthens social order, a kind of trust, by inflicting pain, real and imagined. While he doesn’t directly kill people, he comes close enough. The level of wrongdoing he faces seems to justify a certain recklessness when facing the criminal classes. He is thrown back to the ancient principle of an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. This conception of justice demands a punishment to match the crime—“as he has done so shall it be done to him.”

Reflect on a world where that principle is applied widely in every relationship. When every deed is repaid in exactness, we would have a cacophony of suffering. The crowd presses in, waiting to exact justice. But justice for whom and under whose terms? The Riddler adopts the view that there is no true justice—there is only power and those who wield it. He seeks vengeance against the people and systems that have harmed him. Our crisis of faith begins when we adopt this attitude. Justice as mere retribution is a deeply pessimistic view of the world.

But this is not the only view of justice, and certainly not where the film ends. In a twist, Batman is forced to realize that vengeance is not an adequate response to evil. One cannot fight violence with violence alone. We must also offer mercy. One immediately thinks of Portia’s soliloquy from The Merchant of Venice:

The quality of mercy is not strained.

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

Upon the place beneath. It is twice blest:

It blesseth him that gives and him that takes.

‘Tis mightiest in the mightiest; it becomes

The thronèd monarch better than his crown.

His scepter shows the force of temporal power,

The attribute to awe and majesty

Wherein doth sit the dread and fear of kings;

But mercy is above this sceptered sway.

It is enthronèd in the hearts of kings;

It is an attribute to God Himself;

And earthly power doth then show likest God’s

When mercy seasons justice.

The scepter symbolizes the power of the law to inspire fear in would-be criminals. But mercy sits over justice, revealing an attribute of God, who could have exacted perfect vengeance on all evildoers but elected a different way. His mercy reveals a path for us to follow, one that would prevent our meting out the full force of justice in such a way that it would become indistinguishable from vengeance. Mercy is not a virtue isolated to our individual, spiritual lives. The state best reveals mercy when it incorporates mercy into law.

For those who would say this religious theme is a stretch, look no further than one of the recurring musical themes of the film, “Ave Maria.” Why this theme? The song is tied to the Riddler’s appearances in the film, and more specifically the hypocrisy he sees around him. Frankly, some find the choice offensive, including Brad Birzer in his review. But in reality, for most, hypocrisy now defines our institutions, especially the church. In a flashback, orphans sing “Ave Maria” at Thomas Wayne’s funeral. While the wealthy elite attending the funeral say they care about the “orphan and the widow,” they are in fact far removed from the orphans’ real pain. The Riddler is one such orphan who has been failed by the system. The song, as originally written by Schubert, is indeed a cry for help that in the film becomes a twisted, despairing plea. Again, how can we trust the institutions that are supposed to create and sustain order when they are so clearly corrupt? This is the crisis of faith Batman must come to terms with, since he finds himself agreeing with the Riddler. Even Wayne’s own family is not immune to the deep-seated corruption within Gotham. One critique of the film is that it does not fully flesh out these religious themes. But the themes are present nonetheless, there for us to consider and reflect on.

Back to the theater where I sat surrounded by my fellow members of the mob. How can we move forward in light of the distrust we have in virtually everyone and everything? The two conceptions of justice as displayed in The Batmanilluminate two paths. The first is pure vengeance, in which we find no end to the cycle of evil and retribution. Perhaps this is the current trap in which we find ourselves now. We want our institutions to do something. We want to feel we’re back in control, even if that “control” makes things worse in the long run. But a second path, mercy, provides a way forward for a society sinking under the weight of corruption. This mercy is possible within families, churches, and close communities. These relationships can repair the bonds broken through consistent neglect and even abuse. Not everyone in Batman’s story, or ours, is corrupt. In fact the concept of mercy requires the existence of goodness in the world. To maintain some hope for the future, we do not need to sugarcoat our current state, but we do need to hold on to age-old truths. The Batman mirrors our crisis of faith, yet does not despair.