“I want nothing but usefulness to God and my country” (Diaries, February 22, 1827)

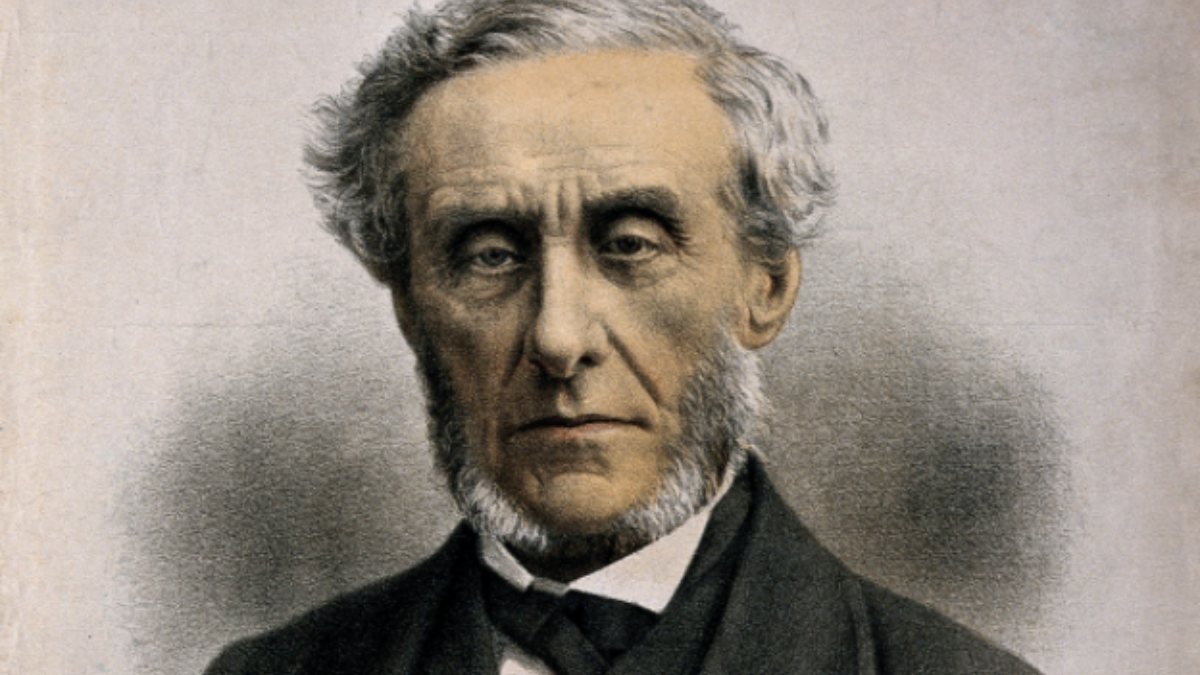

When the funeral procession of Lord Shaftesbury progressed through the streets of London toward Westminster Abbey on October 8, 1885, thousands of people lined the streets, bands gathered to play Christian hymns, and hundreds of banners were held high with Bible verses. The representatives of more than 200 voluntary societies linked to Lord Shaftesbury attended. The Times, in its obituary, described Lord Shaftesbury as “the most eminent social reformer of the present century” and “one of the most honoured figures of our contemporary history.” Who was this extraordinary man remembered in the Anglican calendar on October 1?

Shaftesbury served in one house or the other of the English Parliament for nearly 60 years, from 1826 to 1885, with just one short break of 18 months. He was offered cabinet office by prime ministers of both major political parties of the day, three times in 1866 alone.

And yet he encapsulated the ideal of the Christian philanthropist and evangelist. In his view, religion and life should be united, not separated. He developed a quite remarkable evangelical Christian vision for society. He understood there was a proper function for the state, for government, in protecting the weakest and most vulnerable, especially children. Yet he also recognized that the role of the state was a limited one. Shaftesbury believed in the Christian mission of the conversion of the soul, but also that the Christian faith should shape and transform society. He believed that God had provided the most extraordinary instrument to achieve both these purposes—the Christian voluntary society. Through these societies, large and small, Shaftesbury set out to mobilize and motivate the Christians of Victorian England. He founded schools, chaired missionary societies, and established clubs and societies that provided micro-finance loans for the poor. The list could go on. A committed Tory, he viewed socialism as anathema. He often felt the world to be against him and suffered from an intense introspection that bordered on the depressive. But he was in all things motivated by his Christian beliefs, the centrality of Scripture, and, not least, the principle of faithful discipleship in the light of the second coming.

Anthony Ashley Cooper was born on April 28, 1801. He took the courtesy title of Lord Ashley when his own father succeeded to the earldom in 1811. He retained this designation until he became the seventh Earl of Shaftesbury on his father’s death in 1851. His early family life was difficult, and his relationship with his parents less than congenial. Ashley described his mother as a “dreadful woman.” His own later happy marriage (to Emily “Minny” Cowper) and family life was a significant contrast to what he experienced in childhood.

The really important influence in his early years was the family housekeeper, Maria Millis. She read the Bible to the young aristocrat and taught him to pray. Lord Ashley later looked back saying that under God it was to her that he owed the first thoughts of piety and actions of prayer. He also described in his journals how his eyes were finally “opened” by reading the evangelical writer Philip Doddridge and the impact of acquiring Thomas Scott’s commentary on the Bible. He was slowly embracing the evangelical faith that was to shape his life. As early as 1825 he sought to establish social policy based on the Scriptures.

We see this in his parliamentary campaigns on behalf of London’s climbing boys. Prior to mechanization in the later 19th century, children were used to climb the narrow chimney flues of both homes and factories. To navigate these narrow openings, the younger the child, the better. Sweeps employed children as young as five or six years of age to clean these chimneys, often bonded into the Master Sweep’s employ by poor and desperate parents.

Some of these child laborers became stuck in the chimneys, while others died from inhalation of fumes or the effects of toxic gases from the hearths and the fires. Shaftesbury introduced legislation to Parliament to ban the employment of children as sweeps in 1840, 1853–56, 1864, and in 1875, when the practice was finally outlawed. (One of Lord Shaftesbury’s characteristics was tenacity.) He presented evidence of children being stolen and forced into the sweeps’ employment and the use of pins pressed into their feet or fires lit in the hearths to force the children up the chimneys. The children suffered sores, bruises, deformities, and burns. He described the practice as Satanic. The rich, he said, preferred not to ask how their chimneys were cleaned. The country could never claim to be Christian while such practices continued.

Shaftesbury, then, did not hesitate to campaign for national legislation when that was needed. The real dynamic of his vision, however, lay in the voluntary society. He had a particularly close relationship with the London City Mission, chairing the annual meetings from the 1840s through to his death. The City Mission was founded in 1835 on the principle of taking the Christian faith to the urban poor of London primarily through home visitation. The work grew into reaching out to particular employment groups (such as flower girls and cab drivers), and many missionaries were also involved in founding schools. The City Missionary was in a unique position to watch for and counteract the rise and progress of evil, whether physical or spiritual. Shaftesbury relied heavily on the work of the City Missionaries in his campaigns and concerns, walking the streets of London in their company.

By way of illustration, there is the most remarkable story of Lord Ashley encountering some of the hardest criminals of London. Crucial to Ashley’s approach was the combination of self-help, social provision, and spiritual salvation. In 1848, Ashley was invited by a London City Missionary, Thomas Jackson, to accompany him to a meeting of London’s convicted felons. It must have been a quite extraordinary scene for this English aristocratic gentleman to walk with Jackson into the heart of one of London’s most notorious slums. Three meetings total were held, and a total of 394 convicts attended. Ashley had two aims: to preach the gospel and to assist these individuals in finding a new life. He supported various schemes of emigration designed to help those who had fallen into criminal ways to make a new start. Standing next to Jackson, Ashley preached the faith to his hearers and then sought to persuade them to lift themselves out of the quagmire.

The name Ragged schools seems quaint and old-fashioned, certainly an unlikely choice in the contemporary age. This should not distract us, however, from the impact of this movement in Victorian England. Shaftesbury was associated with the Ragged school movement for over 40 years, and it represented one of the main ways in which he expressed his commitment to Christian social welfare on the ground. The basic aims of the Ragged school—and the numerous individual schools that came under the umbrella of the Ragged School Union in 1844, with Shaftesbury as president—was the Christian education of the poor. The poorest were often excluded from existing provisions, and there was an urgency to teach the Bible. Many of the early Ragged schools came into existence through the efforts of individual City Missionaries. The Ragged School Union’s annual report in 1845 noted the aim of placing poor, destitute children “in the path of industry and virtue.” Here was the wonder of the Christian voluntary society. The same building that housed a Ragged school would also support a school of industry for teaching trades (tailoring and shoemaking being examples) and training for employment and penny banks to encourage the principles of saving, thrift, and prudence. By 1868 there were 257 schools with 31,357 students.

It should be noted that the Ragged schools were not glamorous. They often met in crowded and inadequate conditions, perhaps a room 15 feet square, accommodating 50 to 60 children and eight to 10 teachers, occasionally paid but mostly Christian volunteers. Ashley described one particular school as follows: There was an average Sunday evening attendance of 260, ages five to 20, including 42 who had no parents, seven who were the children of convicts, 27 who had themselves been imprisoned, 36 who had run away from home, 19 who slept in lodging houses, 41 who lived by begging, 29 who never slept on beds, and 17 who had no shoes or stockings.

Growing out of the Ragged schools was the Shoeblack Brigades, founded in 1851 under Shaftesbury’s patronage. The purpose was to provide employment and encourage disciplined lives. The boys’ earnings were split three ways. A third was banked for the future, a third went to the mission to cover costs, and a third was retained by the boys themselves.

For Shaftesbury, the voluntary society was essentially local and relational, neither of which could be said of government interventions, which would not nurture the personal dependence on God the hoped to instill in each of these children along with the virtues of thrift and self-discipline. While he believed that government had the responsibility to protect the most vulnerable, he always insisted that the voluntary principle was the ideal to spread the Christian faith and to act as the locus of social welfare. When in 1870 compulsory state education was introduced in England, Shaftesbury was incandescent. He was deeply skeptical of the march of state power.

The godless, non-Bible system is at hand; and the Ragged Schools, with all their divine polity, with all their burning and fruitful love for the poor, with all their prayers and harvests for the temporal and eternal welfare of the forsaken, heathenish, destitute, sorrowful, and yet innocent children, must perish under this all-conquering march of intellectual power. Our nature is nothing, the heart is nothing, in the estimation of these zealots of secular knowledge. Everything for the flesh, and nothing for the soul; everything for time, and nothing for eternity.

We have barely scratched the surface of this great man’s life. One thing we can say is “Thank God for Lord Shaftesbury.”